The Institute was established in 2010 to research South and Southeast Asian Art, History and Culture.It was founded by Dr. István Zelnik, former high ranking Hungarian diplomat, business man, art collector and sponsor.The core activity of the Institute are research of the antique objects held in the Zelnik Collection, art history resarch and publications, archaeological field work in Southeast Asia such as excavation, historical and epigraphic research, site and remote sensing surveys in relation to the excavation, organistaion and supervision of activities aimed to preseving the built and natural environment. The work of the Institute is goverened by a board of internationaly recognised experts. Its research projects are conducted by Hungarian and international scolars, professors, specialists

Archaeology

Koh Ker

The area lies in the north-eastern part of Cambodia, between the Dangrek, Kulen and Tbeng mountains, some 120 kilometres northeast of Angkor and Siem Reap, in Preah Vihear Province. This hilly area is largely forested, but some of the trees lose their foliage periodically in the dry season. The sparsely populated area of some 81 square kilometres has about 200 temples, smaller shrines and other carved monuments. The area, whose modern name is Koh Ker, presumably derived from the name Chok Gargiar, meaning ‘grove of koki trees’, was the centre of the Khmer Empire in the middle of the 10th century. After his ascension to the throne in 928, King Jayavarman IV moved the royal capital there from the Angkor Plain. His brief, 20-year reign was the golden age of Koh Ker. Some inscriptions call the area “the city of lingas” or “the city of radiance”, because major architectural works were undertaken there under Jayavarman IV that also led to the development of the Koh Ker style, unique within Khmer art. The large reservoir and Prasat Thom, the seven-tiered pyramid temple that is unparalleled in Khmer architecture as well as some forty other temples were all built during his reign.

In 941, Jayavarman IV was succeeded on the throne by one of his sons, Harshavarman II, but after his brief reign, the next king returned the royal seat to the Angkor Plain in 944. Although the area thereby lost its political significance, it continued to play an important role in the religious life of the empire.

Koh Ker was rediscovered in the second half of the 19th century by French travellers, who were followed by expeditions for the exploration of the area. However, along with the explorers, adventurers seeking treasure also arrived and began a systematic looting of the area. In the 20th century, under the Khmer Rouge, the retreating Red Khmers mined Koh Ker. That perhaps partly explains why Koh Ker continued to be isolated and obscure until the area was cleared of mines and tourists began to visit it. Today, the established tourist route provides easy access to some 20 temples and 5 or 6 smaller monuments, but minor paths are available to reach a further 40 ruins. Koh Ker has been on the UNESCO Tentative World Heritage List since 1992.

Excavation in Prasat Krachap

The Hungarian Indochina Company conducted the first exploratory excavations in the precinct of Prasat Krachap in 2011, in cooperation with specialists from APSARA, the Cambodian authority for the protection of cultural heritage. When we selected the area for exploration, we sought a site that was in some respect special among the monuments.

Prasat Krachap, dedicated to the god Vishnu, some 200m northwest of the large reservoir. In addition to having the largest number of Old Khmer and Sanskrit epigraphs, the temple is also architecturally unique with its two enclosure walls and five internal brick towers. The temple is bordered on three sides by three small artificial ponds. The entrance was probably on the western side, where it also has an entrance building that stands outside the enclosure wall.

So far, the research has primarily focussed on the relationship between the temple and its surroundings: whether there was a secular settlement providing services to the temple in the vicinity. We selected the locations for the probes based on the results of a preliminary site inspection. During that inspection, we collected a large number of ceramic finds from the surface, including the area of the ruins on the other side of the road running in front of the temple.

During the two-month excavation we opened a total of 14 trial trenches over an area of 45 square metres, but we also performed a systematic site survey of the entire area of the temple, covering some 12,000 square metres. The excavation yielded information about the internal layers of the area, as well as the surroundings of the buildings. The probes revealed that Prasat Krachap had been built on a natural hill oriented north to south, on its western slope. Presumably, the internal group of buildings was completed first, as construction rubble from them was used for the foundations of the external buildings, the enclosure wall and the entrance pavilion. The excavation also made it clear that the layout of the temple is more complex than previously assumed. The artificial ponds around the temple were probably created during a later phase.

During the site inspection and the probing we also identified the remains of a settlement to the north of the Prasat group of buildings. The hearth and the ceramic fragments found there indicate that there was a village community near the temple.

Further research plans

Our research plan features the systematic archaeological exploration of the entire temple and a part of its environment. We intend to conduct the archaeological research over the next five years in cooperation with APSARA Authority.

However, before opening larger surfaces up, we shall perform a geophysical survey of the area based on the results of the probes. We plan to extend the survey over the immediate and wider surroundings of the temple to a distance of 200-300 metres where, we presume, there was active life and the archaeological material indicates the presence of further remains of buildings and settlements.

We assume that the geophysical survey will allow us to identify some buildings that are only partially known so far, such as the pavilion on the western side, and we are also likely to gather unique information about the residential area that once surrounded the Prasat, its underground features and the foundation structures of now vanished buildings constructed from perishable materials.

Parallel with that work we shall also perform a geodetic survey of the entire area and the buildings, which will also have to include a survey of the surrounding area and detailed descriptions of the buildings as historic monuments. In addition, we prepare a conservation plan for the temple and, prior to the commencement of archaeological exploration, we shall perform the most urgent preservation work. The conservation of Prasat Krachap will be conducted after the archaeological research is completed.

As an important part of the research programme, we shall present the tools, methods and systems of documentation used in the research to our Khmer colleagues at APSARA Authority in the form of on site workshops, to facilitate their learning of how to use non-destructive research methods and tools in practice and to explore the possibilities of those methods in archaeological research.

Cooperation with the APSARA Authority

A royal edict issued in 1995 founded the APSARA Authority for the protection of cultural heritage sites in Cambodia. This was necessitated by Angkor being declared a World Heritage site and the fact that scientific research and conservation work was beginning at Angkor with the participation of international organisations. The cultural heritage protection authority is under double supervision by the Board of the Council of Ministers and the Ministry of the Economy and Finance. The authority was granted extended powers in 1999. Its tasks include protection, management, care, supervision, research, and the conducting and coordination of conservation work at the Angkor heritage sites, as well as at the other World Heritage sites in Cambodia and at the monuments of the Funan and Chenla Kingdoms and the Khmer Empire. In addition, it also protects the natural environment of various areas, preventing illegal deforestation and occupation of land, arranging financing for the maintenance of areas to be protected and also issuing permits for supervising scientific research and conservation work conducted in heritage and archaeological areas.

The Hungarian Indochina Company has been conducting its scientific research and archaeological exploration in cooperation with APSARA since the outset of the Koh Ker Programme. Cooperation takes various forms, from obtaining permits for the research efforts, through professional consultation, to joint research work. In order to implement the programme, commenced in 2008, we initially concluded a three-year cooperation agreement with the APSARA Authority, which was extended for a further five years in 2012. The trial exploration within the precint of the Prasat Krachap temple in Koh Ker in 2011 was an excellent example of cooperation: the work was conducted by our archaeologists and Khmer specialists. During the research, in addition to the exchange of professional experiences, collegial relationships and personal friendships were also formed. During the next five years, we intend to maintain and expand those relationships while also introducing training for a new generation of experts, providing specialist education and site experience opportunities for the archaeologists of the future at the excavation sites. In addition, we also intend to conduct conservation and preservation work in cooperation with the specialists of APSARA in tandem with the exploration of the Prasat Krachap temple.

Lidar

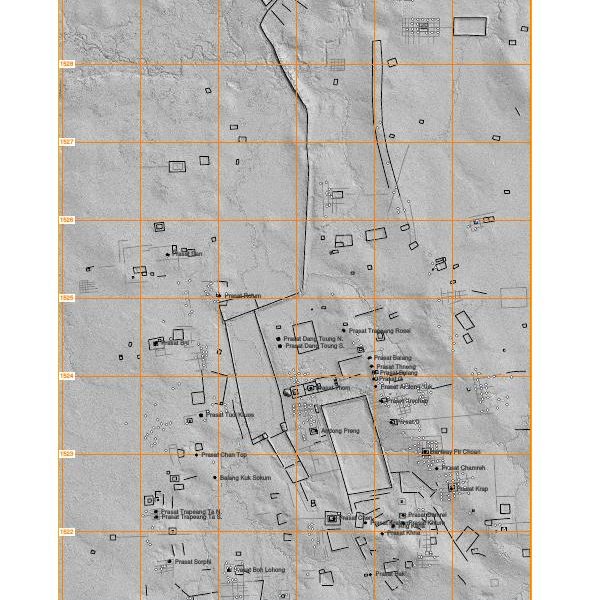

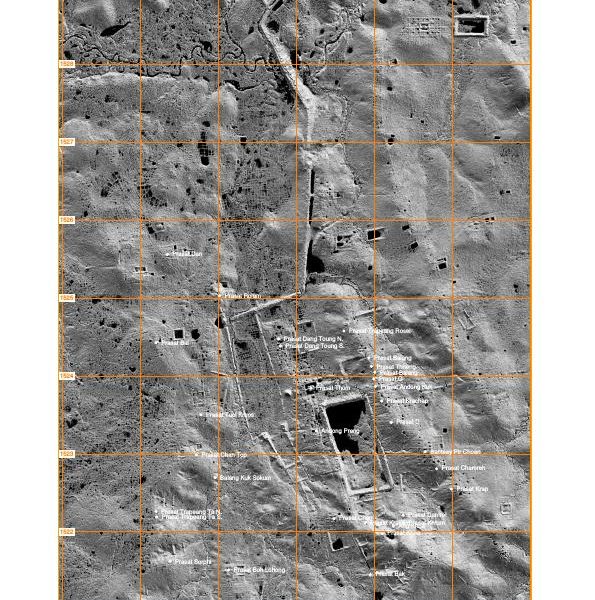

The LIDAR programme is a new Laser based technology permitting to obtain a very significant quantity of data about the entire 67 square kilometre area of Koh Ker. The processing methode in a novel way has permitted to make new discoveries – a ceremonial road and stairs, a stone lion,a quarry, etc. – and also yielded new data concerning the development and construction history of the built environment at Koh Ker. The LIDAR data have also led to new discoveries concerning the known east-west orientation and the 14-degree declination charasteristic of Koh ker, there was also a group of building with an approximetly 6-degree declination presumably from the early period of Koh Ker.

More information about LIDAR Koh Ker below on the link (on the pages 79-103.):

Epigraphy

In parallel with the archaeological exploration of Koh Ker, the Sanskrit and Old Khmer inscriptions there are being translated and interpreted at the Institute. Prasat Krachap, the temple where our archaeological excavations are taking place, has the largest number of inscriptions at Koh Ker, which was part of the reason we chose that temple for our exploration work. The interpretation of the inscriptions on the columns of the temple’s galleries and the pillars of the entrances has been giving our researchers a great deal to think about. The reason is that several of those inscriptions are actually lists of names, and deciphering their significance is one of the most fascinating parts of the research. The Koh Ker epigraphs are being translated and interpreted by the talented young Khmer epigraphist Kunthea Chhom and the foremost authority on Khmer history and epigraphy, the French professor Claude Jacques.

Relevant publication: Chhom, Kunthea: Inscriptions of Koh Ker I. Ed. Zsuzsanna Renner. Publications of the Hungarian Southeast Asian Research Institute 1. Budapest: Magyar Indokína Társaság Kft., 2011. pp. 334.

Our programme concerned with the written relics of Khmer history extends beyond Koh Ker. The research of Cambodian epigraphs is of fundamental importance in the reconstruction of Khmer history, as they constitute the only extant written body of information from the classical period of the Khmer Empire and the kingdoms that preceded it within Cambodia. The history of the Khmer Empire was reconstructed in the 19th and 20th century by French historians based on the stone inscriptions of Khmer rulers and, in some instances, other notabilities. The view of Khmer history thus obtained is completed by some written reports and descriptions of Chinese travellers and ambassadors.

In 2012, the programme of our Institute focussed on the translation of the epigraph of the Sdok Kak Thom temple, which is one of the most important Khmer inscriptions with relevance for history and religion. The Sanskrit language text, which had been translated and interpreted several times before, and which has been the subject of a great deal of discussion and debate, was translated and re-interpreted this time by Tibor Novák.

Artefact inspections

The methods of natural science play an important role within the work of our Institute, both with regard to the study, identification and description of the objects in the Zelnik Collection and the archaeological field work and the associated surveys and tests.

Metal composition tests

We conduct a great deal of laboratory analysis to determine the material composition of the objects in the Collection. At present, we are studying the objects in the Burmese collection, which is not currently exhibited. The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) testing of metal objects provides information about the composition of the alloys used, which allows us to detect incidentally occuring modern alloying additives. Cobalt and Cadmium, for instance, are telltale ingredients; the latter is used to lower the melting point in modern processes. The tests which have a great importance in the valorisation process of the collection have detected no modern alloying additives so far. The metal composition tests are conducted by the Hungarian Precious Metal Testing and Authentication Authority.

Instrumental testing of objects and identification of gems

The microscopic examination of objects primarily yields information about the methods of manufacture. The thorough inspection of the Burmese collection has attested a highly developed metalworking craftsmanship. This is no surprise if we take into account that in Burma, alchemy had developed into a veriteble cult by the 5th century, and, despite religious disapproval, it is still practised today. In addition to the methods of producing metal plates and joining them together to form objects, microscopy also reveals the types of ornamentation and the techniques used in making them, while in the case of cast objects, the quality and technique of the casting can be established using this type of analysis. Through the discovery of the tell-tale details of manufacturing techniques, the tests provide decisive information about the authenticity of the objects as well.

The precious metal jewellery and other objects in the Zelnik Collection are often adorned by gems, and precious stones have also been used on their own to make cut and carved beads of various shapes and colours since prehistoric times. Glass, which was a rarity at the time, was also a popular material that was used diverse ways in the jewelry making of Southeast Asian cultures, often on par with precious stones. Even in the earliest times, glass was imported to the region from Arikamedu in Southern India.

The examination and identification of gems is therefore of prime importance for the description of the objects in the collection. At present, the gems in the Burmese collection are being identified. In Burma, the working of precious stones reached an almost unbelievably high level as early as the Iron Age Samon Valley Culture (from around 300 BCE). The materials used for the etching, colouring and patterning of gems indicate a sophisticated knowledge of materials. Polariscopy and refractometry, accompanied by microscopic photography, provide plentiful information about all these methods.

At the institute, the instrumental tests of objects and the identification of gems is performed by Dr. József Takács, master jeweller, precious metal expert, geologist and Chairman of the Hungarian Society of Precious Metal Workers, formerly a professor at the Budapest University of Technology.